Paperwork: A Brief History of Artists’ Scrapbooks

Andrew Roth & Alex Kitnick

The scrapbook has long been used as a storehouse for memories — to preserve a lock of hair, a sentimental piece of correspondence, a magazine clipping, or a beloved snapshot. Finding a historical precedent in the 17th-century commonplace book, in which bits of scripture might be jotted down alongside literary quotations and recipes, the scrapbook evolved into a highly crafted visual record, a diary not just of thoughts, but also of things. Artists began to engage with the scrapbook in earnest in the postwar period, using the page as variously as the canvas, albeit on a smaller scale. As the title Paperwork suggests, this book explores how contemporary artists have used the scrapbook to forge an intimate artistic identity, in opposition to the bureaucratic, administrative papers that provide official identification.

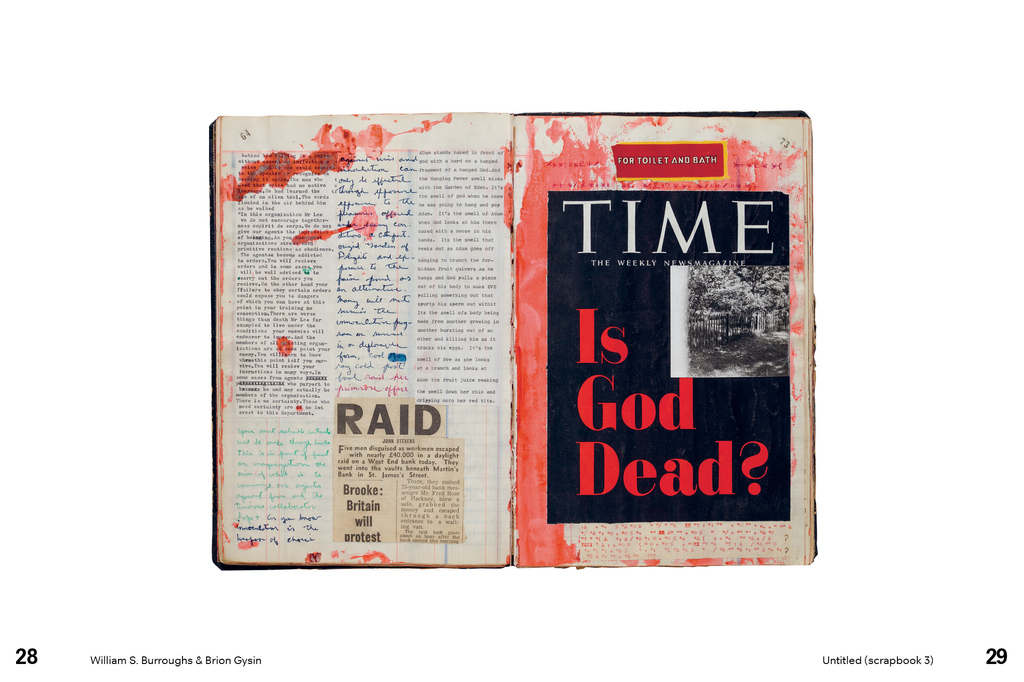

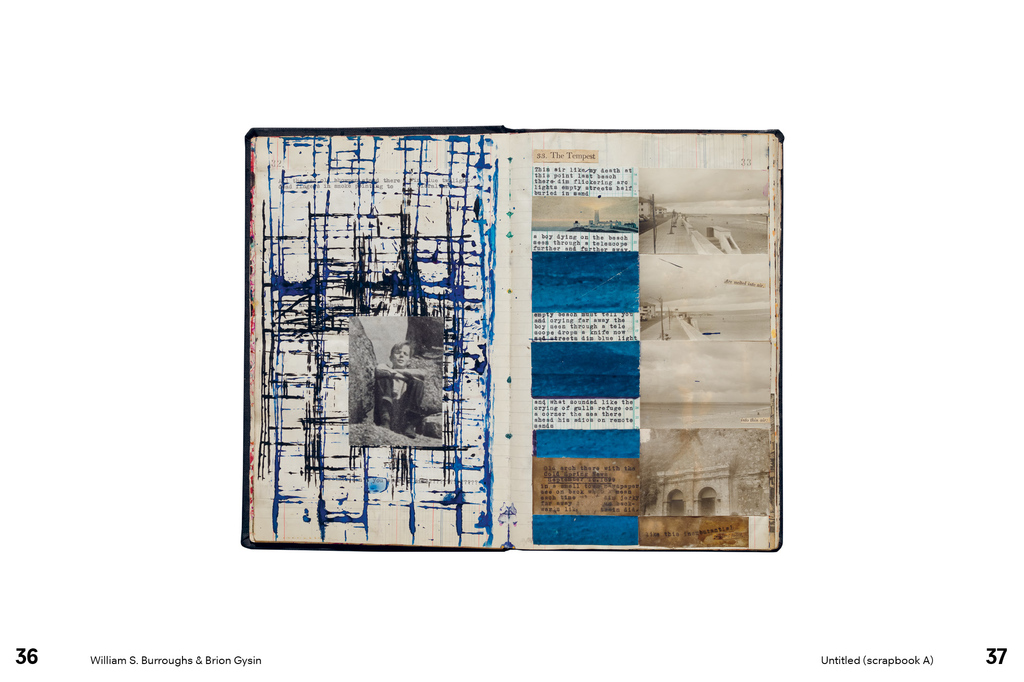

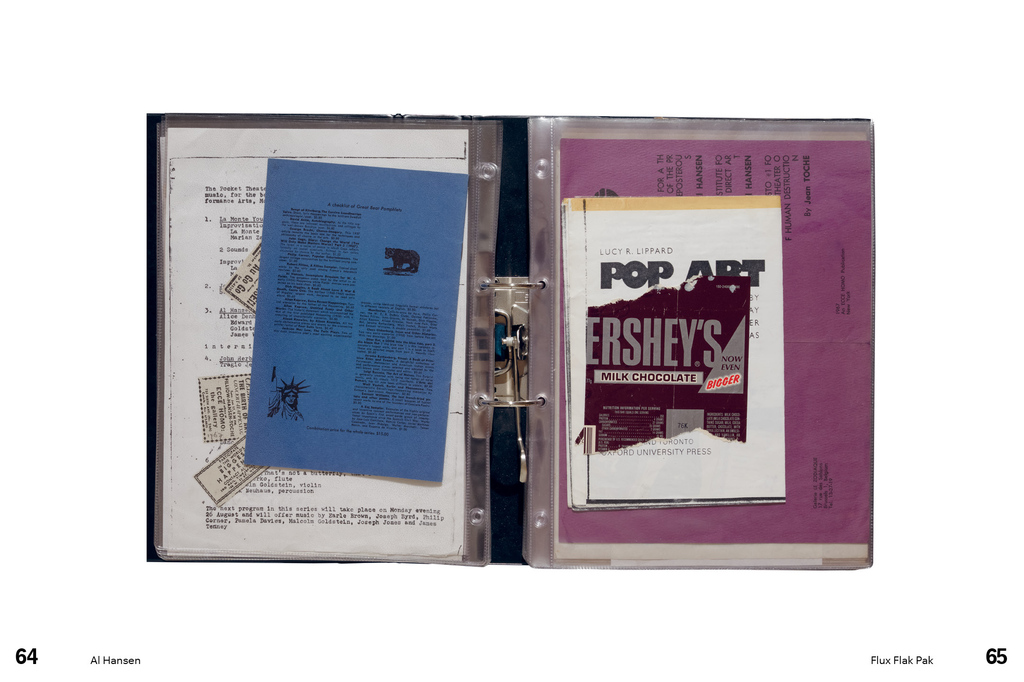

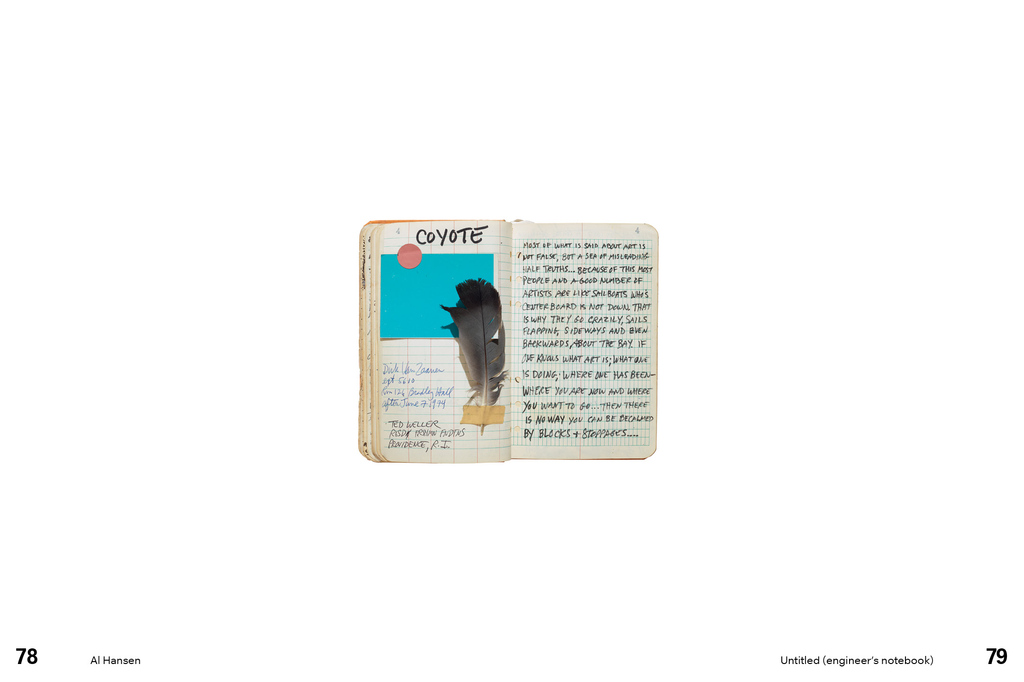

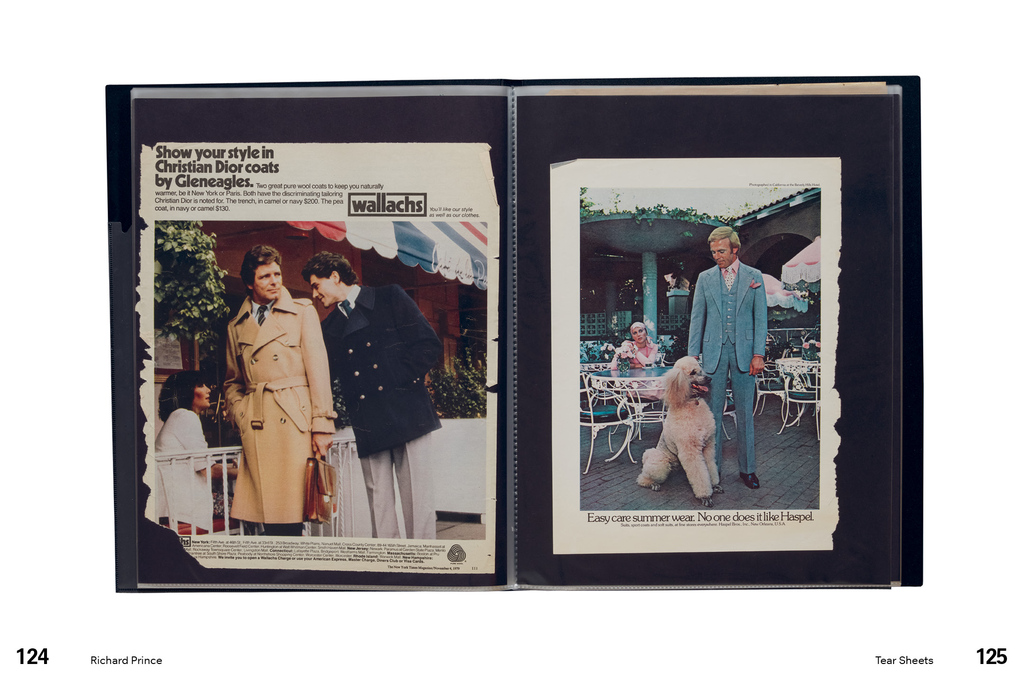

If the conventional scrapbook originally was a place to store memories, the artist’s scrapbook often trades in nascent ideas, both visual and textual, which may or may not grow into a more finished work. Such books allow an informal view into the process of thinking that goes before making; the collecting that comes before facture. William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin (whose three exceptional scrapbooks form the backbone of this exhibition) used oversize books to intertwine visual ideas and threads of stories: news clippings and shards of advertisements woven among watercolor paintings and excerpts from manuscripts — arrangements which fed into Burroughs’s dreams and back out into his cut-up narratives. Other artists, such as Al Hansen, carried small notebooks for organizational jottings, quick sketches, and humorous musings, making collages on the fly and tucking away daily detritus for safekeeping. Richard Prince collected tear sheets from magazines in plastic portfolios, archiving his images of biker chicks and catalog models for later use. Carolee Schneemann kept long-running scrapbooks, documenting both her domestic life and her burgeoning artistic career.

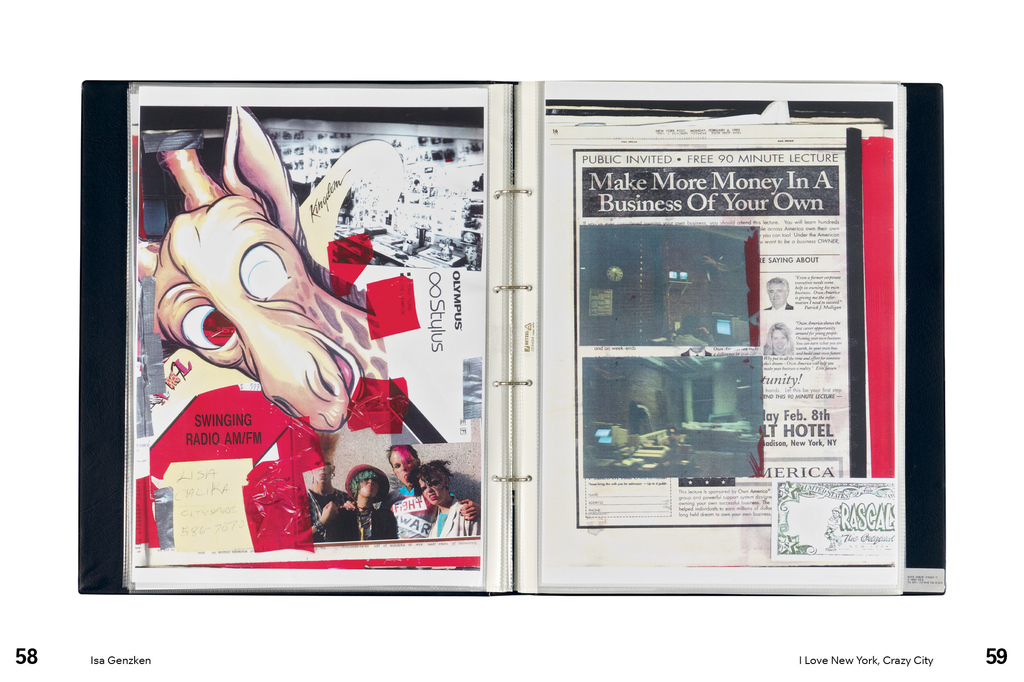

But the scrapbook can also be a finished work itself, in which the tightly conceived and carefully constructed sheets form a complete whole. Isa Genzken’s I Love New York, Crazy City is one such example: made during a year she spent in New York in the mid-1990s, the book is a madcap conglomeration of color snapshots, faxes, and letters affixed to the pages with electrical tape. The French artist Jean-Michel Wicker makes byzantine scrapbooks, often excising pages from store-bought notebooks at the gutter and taping in replacement patchworks of found images, Internet printouts, and hand-lettered phrases. A classic scrapbook purportedly made by Ray Johnson when he was a teenager features kitsch images of babies, puppies, and western landscapes; it was later repurposed in an edition by Brian Buczak, who xeroxed particular spreads, creating degenerated Pop facsimiles.

Paperwork illustrates three to four spreads from these scrapbooks, among others, and includes two essays: “Patterns and Scraps” by Alex Kitnick and “Glue and Cum” by Richard Hawkins, plus fully annotated descriptions of each scrapbook by Claire Lehmann.

First edition, 300 copies.

Large folio, 20 × 15 inches; 156 pages, unbound; 4-color reproductions, all scrapbooks reproduced to scale; housed in a specially made vinyl envelope.

︎︎︎ Exhibition